Getting Started with Redux Saga

This article was originally posted on the Just Eat Takeaway tech blog.

The front end team at Takeaway.com has been working hard to migrate our main web application to a modern JavaScript stack. We are building the new front end application with Next.js, React, and Redux Saga. When we started, my experience was mostly with Redux Thunk and Redux Promise. Redux Saga is quite a different beast, so it took some time for me to understand the underlying context, the general approach, how generator functions fit into the flow, and the pros and cons of using the library.

While on my quest to learn as much as I could about Redux Saga, I was disappointed by the lack of educational resources available. So I decided that since I have some free time due to the whole COVID-19 situation, I can create a guide for getting started with Redux Saga.

For this article, it would be helpful to understand the basic concepts of Redux, such as reducers and actions, but it is not required.

Before we jump into Redux Saga code, let’s go over some fundamental concepts first.

What is a Saga?

I don’t know about you, but I was not aware of the broader programming concept of a Saga before diving into the Redux library. I will describe this concept, as it is the design pattern which Redux Saga is based on.

In the microservices world, a saga is meant to aid in implementing a transaction that spans multiple services or business domains. The saga pattern is designed as a way to handle side effects within an application. The Redux Saga homepage describes the framework as:

A library that aims to make application side effects (i. e. asynchronous things like data fetching and impure things like accessing the browser cache) easier to manage, more efficient to execute, easy to test, and better at handling failures.

As a JavaScript developer who’s spent a fair amount of time sifting through callback-hell, that sure sounds good to me!

This talk by Caitie McCaffrey goes into great detail about the Saga pattern.

As an example, let’s take the event of a user adding an item to their basket. Within our Redux state, we must access:

- the menu context to fetch the menu item info.

- the restaurant context to determine the price of the item, which can differ between delivery and pickup, special offers, etc.

- the basket context to add the item and augment the price total.

- error contexts in case one is thrown (and additionally, any logging services we might want to use).

A quick word about the Generator Function

Redux Saga uses generator functions a lot. I definitely use generator functions the most when I am working with this framework. We aren’t going to take a deep dive into them in this article, but I recommend reading the MDN documentation if you want to learn more.

For understanding the basics of Redux Saga, we only need to know a few things about this particular kind of function. Generator functions allow us to pause our functions and wait for a process to finish, which is similar to the thought process behind resolving promises.

The basic syntax of a generator function looks like this:

function\* myGenerator() {

const result = yield myAsyncFunc1() yield myAsyncFunc2(result)

}A generator function is declared using the asterisk * after the function keyword. The yield keyword tells the function to wait until that line is finished running. In this case, myGenerator will wait (or yield) until myAsyncFunc1 has completed, at which time the function will move on to run myAsyncFunc2, passing in the returned result from the first function.

There’s a lot more to generator functions than we’ve discussed, but this is enough to get you through this article and the basics for Redux Saga.

Our Example

For our example, we will consider the foundations for building a food ordering application. There are certain business domains within this type of app that we need to take into account. We will refer to these differences in logic as our different contexts.

- Menu: items, categories, options or sides, sizes, prices, allergens info, etc.

- Checkout: basket of selected items, total amount, tax, delivery fees, payment methods, vouchers, etc.

- User: saved payment methods, saved addresses, email, phone number, etc.

We will look at a high-level overview of how we would plan out these sagas within our app’s architecture. Which events need to happen in each context? What will be the side effects that we want to handle in our sagas? These are the types of questions we need to ask ourselves when designing our sagas’ layout.

Are you hungry yet? Me too 😋 Ok, let’s go!

The Root Saga

Similar to how reducers in Redux are organized in that we have a root reducer which combines other reducers, sagas are organized starting by the root saga.

function\* rootSaga() {

yield all(\[

menuSaga(),

checkoutSaga(),

userSaga()

\])

}Let’s first focus on the things that might jump out at you.

rootSaga is our base saga in the chain. It is the saga that gets passed to sagaMiddleware.run(rootSaga). menuSaga, checkoutSaga, and userSaga are what we call slice sagas. Each handles one section (or slice) of our saga tree.

all() is what redux-saga refers to as an effect creator. These are essentially functions that we use to make our sagas (along with our generator functions) work together. Each effect creator returns an object (called an effect) that is used by the redux-saga middleware. You should note the naming similarity to Redux actions and action creators.

There’s a long list of effect creators in redux-saga, and we will certainly cover a few. In this case, all() is an effect creator, which tells the saga to run all sagas passed to it concurrently and to wait for them all to complete. We pass an array of sagas that encapsulates our domain logic.

Watcher Sagas

Now let’s look at the basic structure for one of our sub-sagas.

import { put, takeLatest } from 'redux-saga/effects'function\* fetchMenuHandler() {

try {

// Logic to fetch menu from API

} catch (error) {

yield put(logError(error))

}

}function\* menuSaga() {

yield takeLatest('FETCH\_MENU\_REQUESTED', fetchMenuHandler)

}Here we see our menuSaga, one of our slice sagas from before. It’s listening for different action types that are dispatching to the store. For example, when we want to fetch the menu from our API, somewhere in our application, an action will be dispatched with the type FETCH_MENU_REQUESTED. menuSaga is watching for that actionType using takeLatest, and when it sees that action type, it will run a handler function — fetchMenuHandler. For this reason, these types of sagas are referred to as watcher sagas. In summary, watcher sagas listen for actions and trigger handler sagas.

We wrap the body of our handler functions with try/catch blocks so that we can handle any errors that might occur during our asynchronous processes. Here we dispatch a separate action using put() to notify our store of any errors. put() is basically the redux-saga equivalent of the dispatch method from Redux.

You’ll probably add separate error handling mechanisms in your own apps.

const logError = error => ({

type: 'LOG\_ERROR',

payload: { error }

})Let’s add some logic to fetchMenuHandler.

function\* fetchMenuHandler() {

try {

const menu = yield call(myApi.fetchMenu) yield put({ type: 'MENU\_FETCH\_SUCCEEDED', payload: { menu } ))

} catch (error) {

yield put(logError(error))

}

}We are going to use our HTTP client to make a request to our menu data API. Because we need to call a separate asynchronous function (not an action), we use call(). If we needed to pass any arguments, we would pass them as subsequent arguments to call() — i.e. call(myApi.fetchMenu, authToken). Our generator function fetchMenuHandler uses yield to pause itself while it waits for myApi.fetchMenu to get a response. Afterwards, we dispatch another action with put() to render our menu for the user.

OK, let’s put these concepts together and make another sub-saga — checkoutSaga.

import { put, select, takeLatest } from 'redux-saga/effects'function\* itemAddedToBasketHandler(action) {

try {

const { item } = action.payload const onSaleItems = yield select(onSaleItemsSelector)

const totalPrice = yield select(totalPriceSelector) if (onSaleItems.includes(item)) {

yield put({ type: 'SALE\_REACHED' })

} if ((totalPrice + item.price) >= minimumOrderValue) {

yield put({ type: 'MINIMUM\_ORDER\_VALUE\_REACHED' })

}

} catch (error) {

yield put(logError(error))

}

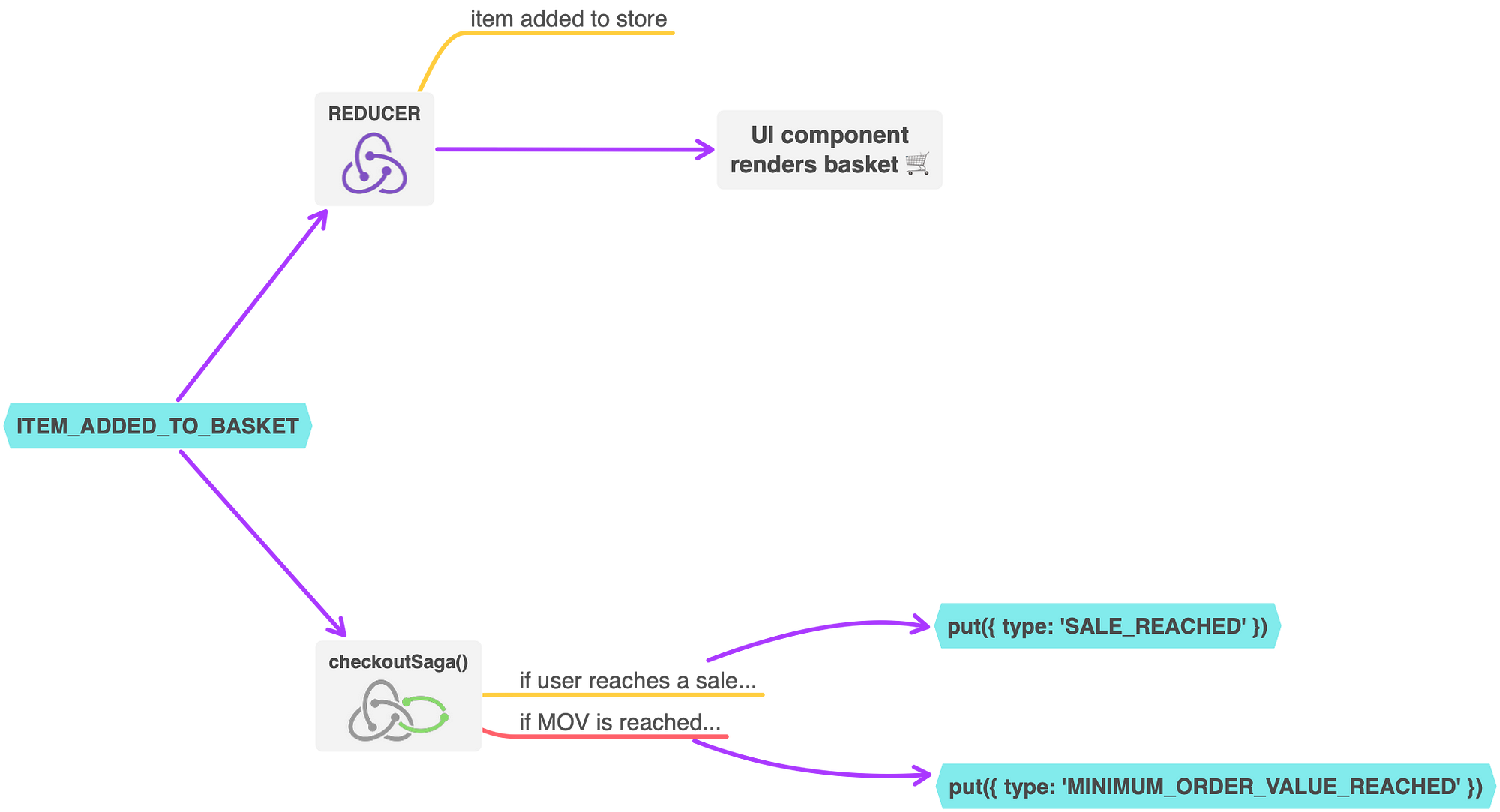

}function\* checkoutSaga() {

yield takeLatest('ITEM\_ADDED\_TO\_BASKET', itemAddedToBasketHandler)

}When an item is added to the basket, you can imagine that several checks and verifications need to be made. Here we are checking if the user has become eligible for any sales from adding an item or if the user has reached the minimum order value needed to place an order. Remember, Redux Saga is a tool for us to handle side effects. It shouldn’t necessarily be used to house the logic which actually adds an item to the basket. We would use a reducer for that, because this is what the much simpler reducer pattern is perfectly fitted to do.

High level visual of the saga flow

High level visual of the saga flow

We are making use of a new effect here — select(). Select is passed a selector and will retrieve that piece of the Redux store, right from inside our saga! Note that we can retrieve any part of the store from within our sagas, which is super useful when you depend on multiple contexts within one saga.

What’s a selector? A selector is a common design pattern utilized in Redux where we create a function which is passed the state and simply returns a small piece of that state. For example:

const onSaleItemsSelector = state => state.onSaleItemsconst basketSelector = state => state.basket

const totalPriceSelector = state => basketSelector(state).totalPriceSelectors serve as a reliable and consistent way to reach in and grab a piece of our global state.

Conclusion

With not much code, we managed to create a structure for handling the events of our food ordering app. When we want to introduce the next domain of our application, we would create a new watcher saga and pass it to the root saga. Then we create handlers to listen for actions and perform side effects.

Scaling this setup is easy and logical, since we don’t have to create complex mental models and spaghetti code in order to introduce new (side) effects into our Redux flows.

Redux Saga is an excellent framework for managing the various changes and side effects that will occur in our applications. It offers very useful helper methods, called effects, which allow us to dispatch actions, retrieve pieces of the state, and much more.

In future articles, we will build a demo application and dive into more advanced concepts. I hope this served as a good primer, and that you now have a solid foundation to get started with Redux Saga.

Got feedback? Suggestions? Just want to say hi? Reach out to me on LinkedIn or Twitter!